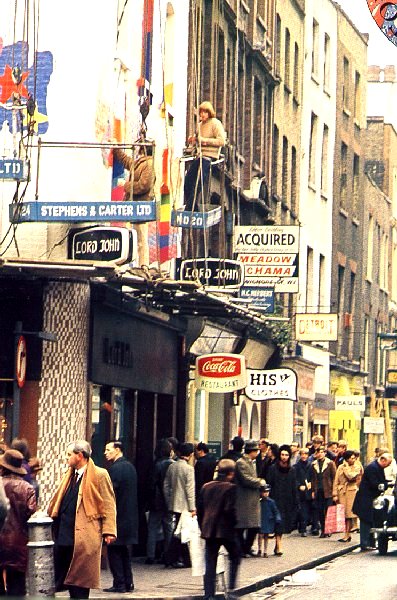

As a young man he showed aptitude in dancing which, with his elegant fashion sense, enabled him to gain employment as a dancer in New York City nightclubs. He became part of the stage act of Texas Guinan and his success led him to Broadway where he again worked as a dancer. He worked in London as a chorus boy in the early 1920s.

Vi Kearney, later a dancer in shows for Charles Cochran and Andre Charlot, was quoted as saying:

Oh yes, I knew him (George Raft). We were in a big show together. Sometimes, to eke out our miserable pay, we'd do a dance act after the show at a club and we'd have to walk back home because all the buses had stopped for the night by that time. He'd tell me how he was going to be a big star one day and once he said that when he'd made it how he'd make sure to arrange a Hollywood contract for me. I just laughed and said: 'Come on, Georgie, stop dreaming. We're both in the chorus and you know it.' [Did he arrange the contract?] Yes. But by that time I'd decided to marry... [Was he (Raft) ever your boyfriend?] How many times do I have to tell you ...chorus girls don't go out with chorus boys.In 1929, Raft relocated to Hollywood and took small roles. His success came in Scarface (1932), and Raft's convincing portrayal led to speculation that Raft was a gangster. Due to his life-long friendship with Owney Madden, Raft was a friend or acquaintance of several other crime figures, including Bugsey Siegel and Siegel's old friend Meyer Lansky. When Gary Cooper's romantic escapades put him on one gangster's hit list, Raft reportedly interceded and persuaded the mobster to spare Cooper.

He was one of the three most popular gangster actors of the 1930s, with James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson. Raft and Cagney worked in Each Dawn I Die (1939) as convicts in prison. Raft advocated for the casting of his friend, Mae West, in a supporting role in his first film as leading man, Night after Night (1932), which launched her movie career. Raft appeared the following year in Raoul Walsh's period piece The Bowery as Steve Brodie the first man to jump off Brooklyn Bridge and survive, with Wallace Beery, Jackie Cooper, Fay Wray and Pert Kelton.

Some of his other films include If I Had a Million (1932; in which he played a forger hiding from police, suddenly given a million dollars with no place to cash the check), Bolero (1934; in a rare role as a dancer rather than a gangster), an adaptation of Dashiell Hammett's The Glass Key (1935) (remade in 1942 with Alan Ladd in Raft's role), Souls at Sea (1937) with Garry Cooper, two with Humphrey Bogart: Invisible Stripes (1939) and They Dive by Night (1940), each with Bogart in supporting roles, and Manpower (1941) with Edward G Robinson and Marlene Dietrich. Although Raft received third billing in Manpower, he played the lead.

The years 1940 and 1941 proved to be Raft's career peak. He went into a gradual professional decline over the next decade, in part due to turning down some of the famous roles in movie history, notably High Sierra and The Maltese Falcon; both roles transformed Humphrey Bogart from supporting player to a major force in Hollywood in 1941. Raft was also reported to have turned down Bogart's role in Casablanca (1942), although according to Warner Bros. memos, this story is apocryphal.

Following the release of the espionage thriller Background to Danger (1943), a film intended to capitalize on the success of Casablanca, Raft demanded termination of his Warner Brothers contract. Jack Warner was prepared to pay Raft a $10,000 settlement, but the actor either misunderstood or was so eager to be free of the studio that it was he who gave Warner a check in that amount.

During the 1950s he worked as a greeter at the Capri Casino in Havana, Cuba, where he was part owner along with Meyer Lansky and Santo Trafficante. In 1953, Raft also starred as Lt. George Kirby in a syndicated television Police Drama titled I'mn the Law, which ran for one season.

He satirized his gangster image with a well-received performance in Some Like it Hot (1959), but this did not lead to a comeback, and he spent the remainder of the decade making films in Europe. He played a small role as a casino owner in Ocean's Eleven (1960) opposite the Rat Pack. His final film appearances were in Sexette (1978), reunited with Mae West in a cameo, and The Man with Bogart's Face (1980).

Fred Astaire, in his autobiography Steps in Time (1959), says Raft was a lightning-fast dancer and did "the fastest Charleston I ever saw." Ray Danton played Raft in The George Raft Story (1961), which co-starred Jayne Mansfield.

In the 1991 biographical movie Bugsy, the character of George Raft was played by Joe Mantegna.

Raft has two stars on the Hollywod Walk of Fame, for contributions to Motion Pictures at 6150 Hollywood Boulevard, and for Television at 1500 Vine St.

George Raft married Grayce Mulrooney, several years his senior, in 1923, long before his stardom. The pair separated soon thereafter, but Grayce, a devout Catholic, refused to grant Raft a divorce, and he remained married to and supported her until her death in 1970. A romantic figure in Hollywood, Raft had love affairs with Betty Grable, Marlene Dietrich, and Mae West. He stated publicly that he wanted to marry Norma Shearer, with whom he had a long romance, but his wife's refusal to allow a divorce eventually caused Shearer to end the affair.

In 1965, Raft was indicted for, and pled guilty to, income tax evasion and could have ended his life behind bars, but the court proved merciful when he wept before the judge, begging that he not be sent to prison, and he was sentenced to probation.

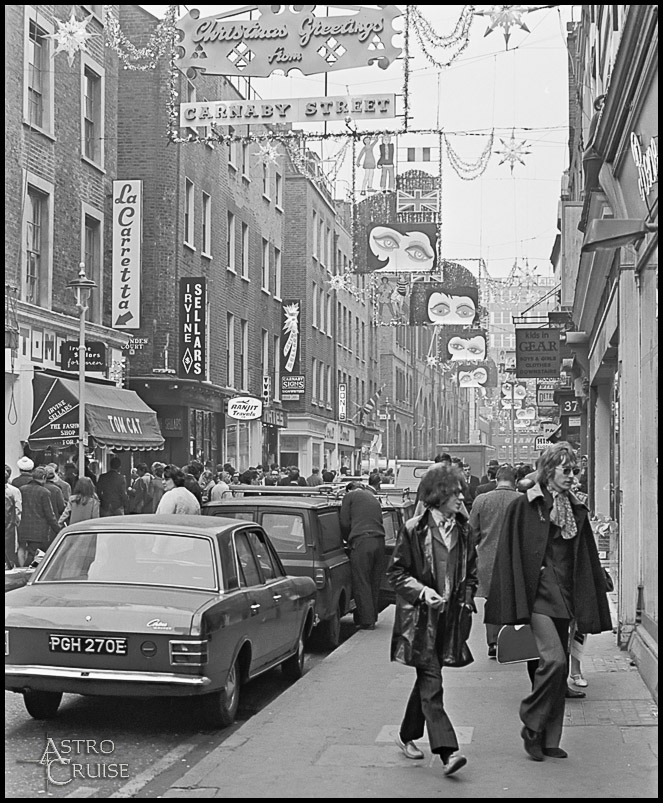

In 1967 he was denied entry into the United Kingdom (where he had been installed as Casino Director at a casino known as "The Colony Club") due to his underworld associations.

Raft died from Luekaemia at age 79 in Los Angeles, California, on November 24, 1980. He was interred in Forest Lawn - Hollywood Hills Cemetary in Los Angeles.